Can Fall Protection Increase Productivity?

December 9, 2024

The pros and cons of using fall protection in the workplace sparks a surprising amount of debate among people who work at height. At first, it can seem like there are a lot of rules and regulations that need to be followed. And the process of obeying those rules and regulations can feel like it is cutting into productivity in the workplace. Even though there are some initial investments that need to be made for fall protection, the future of any business will actually be more productive than a business operating without fall protection.

Healthy Workers = Healthy Business

Any team is only as successful as its weakest player. Although that may seem like an exaggeration, this concept is very valid when discussing workplace falls. If a worker gets injured after falling while working at height, they will either not be able to perform their regular duties as effectively as they once could or they will not be able to work at all. In either scenario, there has been a decrease in the productive capabilities of the person who has been injured from falling while at height. And a decrease in one worker’s production places more stress on the entire team which has to work harder to make up for the loss.

Paperwork Takes Time And Time is Money

Whenever a fall occurs in the workplace, there is a tremendous amount of paperwork and correspondence that follows. Safety managers and any involved employees will need to file internal accident reports, meet with people from OSHA, file medical reports, send documentation to worker unions where applicable, and communicate with any other groups that may apply to the situation (ex: emergency response personnel or another company that was also involved with a particular project). Collecting and compiling all of that information takes time. And filling out those different documents means that there is less time for the regular, more lucrative, workplace duties.

Movement Within The Workspace

The height at which someone is working will play a large role in the way they move around their workspace. A worker who would typically power walk when they are walking on the floor will (presumably) move a little more slowly if they were trying to scale a cell tower. When a worker is using a fall protection system, they might find that they have more confidence to move quickly and more efficiently through their workspace at height. This confidence stems from knowing that the fall protection system is there to protect them and that they can move at height with general ease.

Insurance Costs

Insurance companies will be cautious about the potential risky investment in a company that has had a worker get injured from a fall at height. And if a workplace is a high-risk investment, it is going to have higher insurance costs associated with it. On the other hand, if a workplace displays that it is a low-risk environment because it utilizes fall protection systems and other safety devices, then an insurance company will be more likely to provide a lower cost for coverage.

OSHA Fines and Inspections

Depending upon the severity of the fall incident, there are different levels in which OSHA will be involved. In general, a business will probably receive a citation after a fall event where a worker is injured, but OSHA may only deliver a citation if the business failed to provide fall protection when they knew that a fall hazard was present for workers. In the very unfortunate circumstance that a fall event results in a worker fatality, OSHA will need to conduct an investigation. OSHA investigations can consist of long meetings involving any of the people who were associated with the fall event, worksite evaluations, and a substantial amount of paperwork. When employers and employees need to be involved in an OSHA investigation, productivity can be significantly decreased.

Not having a fall protection system in place for people who work at height is a very dangerous way to conduct a business. There are far too many factors in a fall event that could put the success and productivity of employees and a company at risk. Because there are so many things that can be negatively impacted by an unprotected fall in the workplace, it is clear that implementing an appropriate fall protection system is a worthwhile investment.

Workplace Safety Increases, Not Decreases, Your Productivity

The relationship between safety and productivity has a perception problem in American workplaces.

In 2015, the National Safety Council found that one third of American workers believe that their employers place a higher value on productivity than they do on safety. Given the choice between putting resources towards a safer work environment or towards increased output, the perception goes, managers would rather improve production. Perhaps not surprisingly, workers in high-risk industries arrive at this conclusion far more often than their relatively safer peers. 60 percent of construction workers and 52 percent of those in the agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting fields felt that management valued the product more highly than the producer.

The Occupational Health and Safety Administration’s numbers seem to back up employee attitudes. 24 percent of all workplace fatalities in 2015 came from construction jobs, and three of the top 10 most frequently violated OSHA standards also involved construction-related categories. An obvious conclusion would be to push for increased safety standards, but perhaps the problems are enforcing the current standards and that companies ultimately value production over worker safety. Mike Rowe, host of the Discovery Channel’s “Dirty Jobs,” inadvertently made the case for wary employees when he scoffed at increased safety standards while on the job. “Making money is more important than safety—always.”

You might think having to choose between safety and productivity would be a tough position for a manager to be in.

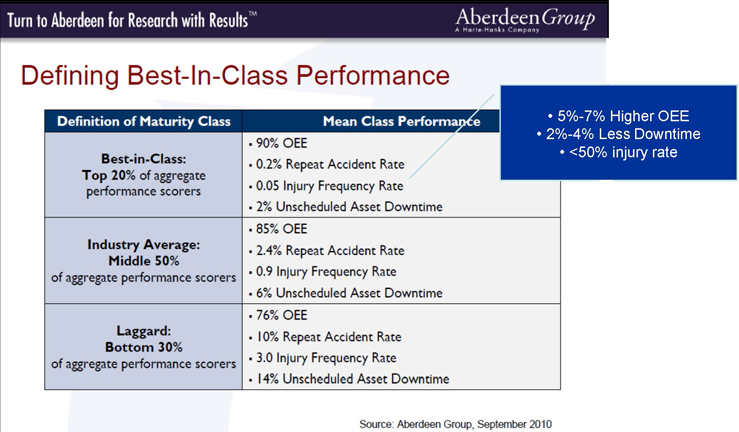

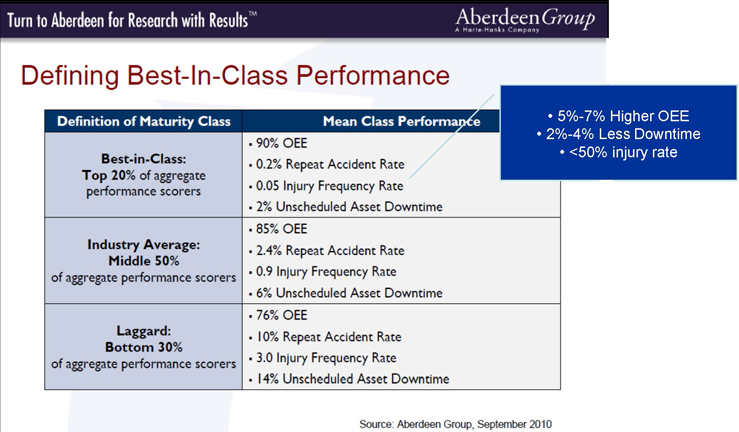

Except that the data suggests it’s no choice at all. Taking a deeper look into the data reveals an unexpected and certainly very encouraging twist.A few years ago, Steve Ludwig sampled data to compare companies with the highest levels of efficient output to those with the lowest frequency of injury. He used statistics from Rockwell Automation’s Safety Maturity Index, which defines the relationship between safety and productivity. His conclusions should open the eyes of any manager who may still cling to any sort of belief that productivity suffers when paired with an emphasis on safety.

Ludwig discovered that Best in Class companies—those that score in the top 20 percent of aggregate performance scores—were also the companies exhibiting the lowest injury frequency rate. In fact, their injury frequency of 0.05 percent was 18 times better than average and 60 times better than the worst performers.

The explanation? “Best in class companies understand that safety and productivity are complementary,” Ludwig said. “If we can reduce injury rate by half, then we can also increase both overall equipment effectiveness and unscheduled downtime.”

Let’s unpack that a bit further. Sure, a company could save money and hours by ignoring a safety hazard or by pushing a review a few months past the deadline. By forgoing any downtime associated with a brief work stoppage, they increase their output by a fraction and are pleased if the workforce goes home healthy. Companies that behave this way tend to equate safety with the absence of accidents and end up tricking themselves into thinking that the precautions they’re taking are sufficient, when in reality, all they’ve done is gotten lucky for longer than usual. It’s a short-term thought process that parallels dangerously with tragedy and ultimately results in injury, stoppage, and loss.

On-the-job accidents actually account for significantly more loss than adherence to safety standards ever could. Consider the National Safety Council’s infographic on the True Cost of Workplace Injuries. Losses include far more than a worker’s recovery time or damages, not to mention personal loss to the workers and their friends and family. Administrative costs, fines, and medical bills factor in. An inexcusable accident in the hands of a savvy social media activist could be a nightmare for public relations staff, particularly if the injury is not the first of its kind. Indirect variables, such as prestige and the company’s desirability as a landing spot for potential employees can also suffer, as they hinge upon having clean, marketable reputations.

Conversely, the Best in Class companies Ludwig referenced take a different approach. They balance production and safety using a concept called “safe production” rather than putting the two in competition. A company should weave worker safety with safe production into the fabric of its culture. This merging can be done by including an emphasis on worker safety in its job descriptions and by talking about worker safety both formally and informally. Expectations on the project level and constantly reviewing and improving safety standards help companies reduce their accidents and see the highest, most consistent levels of production.

In other words, ensuring that a workforce is informed through daily action, feels secure, and is able to come to work every day without suffering injury or seeing others do so is the most effective way to keep your production levels high. And a healthy, productive workforce is the best way to combat any perception problem.

Categories

Share this post

Let us help you

Contact us today to find the perfect product fit for your job